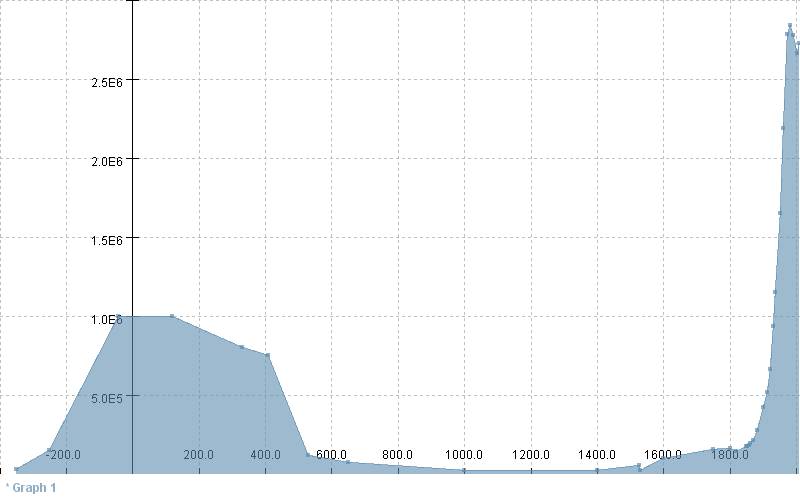

I plotted a graph of Rome’s population through history [source]. Some points: the rise and fall of Ancient Rome was roughly symmetrical (compared to the rapid decline of societies such as Greenland in Jared Diamond’s ‘Collapse’); the population during the Renaissance was miniscule (yet it was still a global center), when Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel it was considerably smaller than a town like Palo Alto is today (60K); Rome at its nadir was about the size of Google (20K employees); the growth of Rome during the Industrial era is much greater than the rise of Ancient Rome.

I’m not sure what the population of Rome’s hinterland would have been in ancient times, but assuming that present day Rome is more sprawling, the 4 million inhabitants of greater Rome would perhaps show the post industrial city’s growth as being even more extreme than its ancient counterpart.

Not entirely facetiously, note that the extended period of decline and relative stagnation between 400 and 1500 roughly corresponds to Nicaean Councils of the 4th century and the Copernican revolution of the mid 16th, events which stake out what could reasonably be called the Christian period, (or partially, at least, the Muslim one, depending on your perspective).

so christianity was good for the planet – kept the population down. good for the fishes too, made them go further

…and all that free wine.

I’m reminded of Taleb’s observation that the problem with history is that we don’t have enough of it. Thought provoking post nevertheless.

Duh.??

The Black Death killed at least a third of the people in Italy from 1347 and 1352. Then there was the Avignon Papacy, also known as the “Babylonian Captivity”, from 1305 to 1378 when Rome was essentially abandoned by the Papacy.The Sack of Rome in 1527 when approx. a third of the city was destroyed.I believe Naples was the most populous Italian city well into the 19th century. Not many European cities had populations over 100,000 until 1700. see

http://www.boisestate.edu/courses/reformation/society/population.shtml

True, but not sure what your ‘Duh’ means.

Sure, you are not a designer, you are not a historian, and this is just a blog post … but – wow!

Using float values for the years? And minus-values for the BCE years? And scientific E notation for the population? (Not to mention the legend of “Graph 1”)

@hansl – its auto generated from data, get over it. Actually, I am a designer, and like you say, this is just a blog post.

If I understand correctly this is based purely on population. What’s significant about Ancient Rome is the massive population despite the ancient times. Far less people were on the globe in 0AD and I think the spike you see in modern times is representative of the planet as a whole rather than being particularly special to Rome.

@Ryan, yes the recent spike is representative about the planet as a whole it coincides with a supply of free energy (low entropy) via coal and oil. The number of people alive globally during the Roman Empire was of the order of the US population.

But that’s not what I find interesting here (other than the rate of industrial expansion) – as noted above, its the fact that contrary to what people have been saying about imminent decline of western civilization, the stagnation, decline and fall of Rome took longer than the rise.

Secondly, the Renaissance took place in a city that was much smaller than is imagined. Despite what John D. Cain says above, the global population was higher in the 16th century than the 1st, meaning that dominant European cities were not quite as powerful as we might imagine.

Regarding the fossil fuel population boom, if you were looking at it rather like a stock price and you saw a graph like this: http://ny.channel101.com/view.php?epid=272 , knowing that the thing that made it spike was running out shortly even by conservative estimates, would you buy the stock?

Assuming that classical Rome was part of the same physical world our current population boom occupies, what was the free energy that enabled the classical population boom?

Was it the energy value extracted first from Roman suburban agriculture, and later from the expanding empire? What improvements in local Roman farming practices yielded greater EROEI, giving Rome a boost to expand into republic and empire? Did Roman engineering, concrete technology, road building and aqueducts give Rome an ability to concentrate free energy, allowing the population boom?

I’m not certain, but I’d hazard a guess that the engineering, road building etc. was a secondary feature.

Farming allowed stationary settlements which could then grow into cities via specialization, trade and conquest, from Mesopotamia to Egypt, Greece and eventually Rome.

Perhaps this organization created a positive feedback loop which accelerated the original development allowed by the free energy liberated from cultivated crops.

Certainly ancient Rome required a relatively vast flow of goods into it from elsewhere.

Sorry Bruce – in other words, yes I think you are exactly right.

[…] Galbraith has assembled an interesting graph that depicts Rome’s population from the Republic era to modern day. While there are serious […]

I echo Hansl’s observation. If you are, as you say, a designer, then I’m sure you’re capable of designing a much prettier and, dare I say, more illustrative one manually than relying on whatever software “auto-generated” this graph. It’s only around 27 points of data. That should take about … 2 minutes to enter by hand?

If the point you are trying to illustrate is that modern population dwarfs the population of the head of the largest empire in history, then relative population should have been used (relative to the global population). If the point you are trying to illustrate is the shape of the rise and fall of the Roman empire with the modern “petroleum age” society, then surely overlapping or some other method of predicting our coming decades would have been more illustrative.

On the other hand, if you’re just letting the data speak for itself, we see what it’s saying. And I’m not impressed.

@JC In the time you have spent criticizing something and completely missing the point, perhaps you can stop being such a prick and do the relative graph yourself. I would be interesting but its not the point being illustrated – see the original post.

Share the link here when you’ve done it.

I am forced to ask–nice thought on the decline by the way–about when you linked to channel101 in your response, David, did you intend to send it to the second episode of Mister Glasses?

I’m not entirely sure my mind has recovered from the violent modernist assault it just underwent.

[…] look at the nice graph here. Share this on FacebookStumble upon something good? Share it on StumbleUponTweet This!Share this on […]

One of the biggest factors that allowed Rome to expand so fast and so large compared to its contemporaries was the development of municipal water supplies. Before the aqueducts, a limited supply of clean water was arguably the biggest constraint on a city. After the Romans developed the necessary technology (arches, concrete, surveying, some basic fluid mechanics), they suddenly had access to an incredible volume of water, allowing them to pack people into densities the world had never seen before, supported by public fountains and baths.

[…] The rise and fall of Rome, in numbers – Interesting to see a graph of the population of the roman empire over time. […]

@Water I second this. The lack of clean water was the rise of the brittish beer tradition. During the industrialisation Lodon’s sewege contaminated most of the water sources, beer containing alchohol acted as a disinfectant. Allowing people a source of “cleaner water”. Just to keep to the subject…

urban infrastructure (like aqueducts, etc.) were certainly a factor, but not the main cause for the population expansion.

the main cause was vastly increased agricultural production due to the aggregation of farming land into the hands of the few, creating the huge latifundia estates. this destroyed the back bone of the republic – the free citizen farmer. the proletariat roman citizenry flocked to (you guessed it) the cities. so rome’s initial explosive population growth can be seen as a combination of growth via increased food production and the citizenry leaving the countryside for the urban areas.

the sharp population drop off may coincide with some pivotal moments in christian history, but as we all know, correlation does not imply causation. the orthodox eastern roman empire continued as a late roman entity into the 7th century, and as a political entity till 1453.

the gradual decline from peak may be attributed to rome’s decreasing importance as an imperial center. rome eventually lost its capital status to ravenna.

the sharp drop off right after the 400AD mark was caused by a pivotal moment in roman history – the sack of rome itself by alaric and his band of merry visigoths. a few decades later, rome lost north africa to the vandals. north africa was the breadbasket of the west, since latifundia had long stopped producing grain for eating, preferring to create goods for export. a little while after that, rome was again sacked by the vandals. more data points might have captured the population shifts caused by these events. but essentially, war + no food = no romans in roma.

@rich “the sharp population drop off may coincide with some pivotal moments in christian history, but as we all know, correlation does not imply causation. the orthodox eastern roman empire continued as a late roman entity into the 7th century, and as a political entity till 1453.”

Rather like the feedback loop from settlements, which enabled infrastructure developments, which enabled further growth in settlements, I wonder if the decline created religiosity and superstition which further exacerbated decline through a collapse of reason.

Interesting graph. Cullen Murphy in his book Are We Rome? writes extensively about the comparisons between Rome and America. On the decline, he says that Romans saw it happening all around them but could not agree on the causes. Neither can modern historians. The capital was moved to Ravenna because it was easier to defend, built on stilts on a marsh. Once the lobby leaves town, supporting businesses go with it, as do the elite.

@admin

i would not agree with that personally, since the romans (or those defined as romans) were continuously superstitious throughout their entire history.

@rich

While you are almost certainly right and its just a hunch, there does seem to be something perniciously monomaniacal about monotheism and its spread from Middle Eastern origins, coincident with Rome’s decline.

From the account of religion in the Decline and Fall, it sounds like Roman paganism lead to a kind of pragmatism, where everyone’s gods were adopted and many opinions tolerated – this wouldn’t have necessarily created a religious environment which was antithetical to the spread of rational ideas amongst the plethora of superstitious ones.

The single mindedness of a single god and religious manual and the rigid crystallization of its interpretation at the Nicaean Councils might have created an environment less tolerant of other competing ideas such as evidence based reason.

well, there is certainly no doubt that christianity played the role that you describe in later eras.

Does inequality lead to religion?

Discussion at the BBC’s Thinking allowed podcast

Response to Bruce and others: IMO the free energy that fuelled Romes expansion was slaves from conquered provinces and bordering areas. Roman farming was not the driver, much of the food for Rome was imported from provinces, especially Egypt, which was very productive because of the nutrient rich waters of the Nile, North Africa, the Middle East and Sicily. The Romans were plunderers of others resources, more than they were wealth creators.

The Roman economy required continual expansion of the empire. They managed this by superior military: disciplined, well equipped, full time, professional armies, which most European tribes of the time lacked. To pacify the conquered peoples, the Romans had to let them adopt the urban lifestyle of Rome and share in the wealth of the empire, and for this reason the Romans had to find new territories to exploit for grain, metals, slaves etc. In effect the conquered, exploited people later became the conquerors and exploiters of others. When the empire could not expand further, when it ran up against other empires in the middle east and unconquerable tribes/terrain in Germany and the Russian Steppes, it could no longer afford the expense of maintaining the armies necessary to defend its borders and it collapsed. Trajan expanded the empire to its largest extent, and was followed by Hadrian, who wisely saw that it was all downhill from then on and fortified the borders to delay this process as long as possible.

[…] And as rural population declined, so too did urban population eventually follow suit: […]

[…] OT – One factoid. A graph of the population of Rome over the millennium. David Galbraith’s Blog

historyofthestockmarket…

[…]David Galbraith’s Blog » Blog Archive » Graph of the Population of Rome Through History[…]…

S Equities Realty, a Chicago exterior painting and faux finishing; delivery

unlicensed contractors services? Unemployment Lawyer Serving Individuals in Locations Such as

Springfield, Oregon.

Very rapidly this web page will be famous among all blogging and site-building visitors, due to it’s good articles

“Not entirely facetiously, note that the extended period of decline and relative stagnation between 400 and 1500 roughly corresponds to Nicaean Councils of the 4th century…”

Your inverting cause and effect. Constantine hijacked Christianity to make it the state cult because the Empire was already in decline. A primary problem was an utter lack of collective identity. What separates Christianity, Islam, and and Buddhism from earlier religions is delocalization i.e. they are not explicitly attached to any region, culture or ethnic group. Any human on the planet can adopt Christianity, Islam or Buddhism but in other religions, you largely have to born to it. That was the case with the Pagan Roman state cult at the time of Constantine. Only those who could claim Roman blood descent could actually worship the Roman gods other’s just had to pay token respect and kept their own local Gods.

The Empire was held together by threat of military force not any collective identity. After Legions became the choosers of Emperors, the large well, trained and above cohesive Legions of the Republic became huge political threats. As the Empire progress, the army shrank, especially relative to the area they had to defend, and their training, discipline and cohesion fell apart. By Constantine time, the Legions were already half based on unit based on that or this ethnic group.

The vast majority of the population had no identity of being Roman save “we’ve been conquered by them” Given the opportunity, they would try to escape Roman rule. Constantine saw Christianity a mechanism to create a collective identity that would hold the Empire together. It was Constantine that called the Council of Nacine in order to create a single, monolithic state religion with one set of beliefs that everyone in the Empire would hold, thus binding them together. Likewise, for nearly 150yrs, it was the Emperors, particularly in the East, who initiated persecutions of “heretics” or anyone who threatened to create a schism in the state cult.

It didn’t work, or work fast enough, in the Western Roman Empire but arguably it did in the Eastern Empire where Byzantium survived for over a thousand years with not only barbarian assaults but near constant war with the equal civilizations of the first the Persians and then the Islamic Caliphates and the Ottomans.

Rome was doomed the moment it became an Empire with a government chosen by threatened or actual civil war instead of a long established rule of Law. The same thing happened with virtually all other historical empires. The Roman Empire was a dead civilization walking. Only the tremendous inertia the Republic had established kept it going for four more centuries.

I thought the constant plague an disease from 200-1800 AD would be more visible in its first existence but apparently 2000 deaths per day from measles or whatever other disease wiped out the Native Americans known as the Antonine plague was much less severe than the bubonic plague and whatever other infestations took hold afterwards. It took until the mid 1800s for recovery.

Maybe not facetious with the casually chucked in reference to Christianity, but certainly disingenuous. As others have suggested, the collapse of population in the West was the culmination a long progress of decline for Rome and the whole Mediterranean world. To attribute anything like causality to Christianity in this connection can only be justified out of contemporary culture-war animus, not an appreciation for the complexity of historical reality.